Worker welding La femme à la clef (La Taulière) in front of Picasso at ‘La Californie’, Cannes, 1957. Photograph by David Douglas Duncan. © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / image RMN-GP © David Douglas Duncan

From sketch to object

Picasso and the applied arts

From a textile pattern made by William Morris to a lamp designed by Mariano Fortuny, from a perfume bottle devised by Kazimir Malevich to Gerhard Richter’s stained-glass window for a cathedral, the raison d’être of the applied arts is based on the artistic conception of an object that has been created for a specific use in people’s everyday lives.

The artist presents a design or prototype which, through collaboration with a craftsperson, manufacturer or other artist, materialises into one or several replicas of an object generally through an industrial manufacturing process.

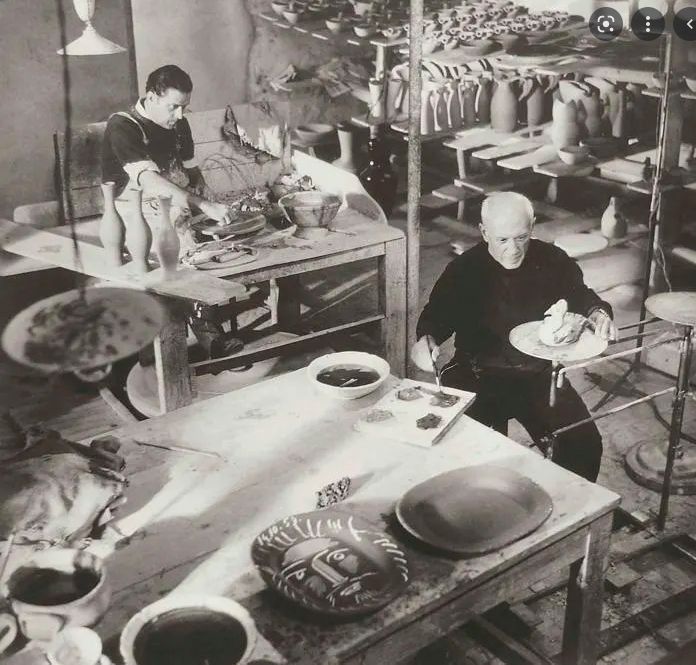

In Madoura, October 1953. Photograph by André Villers. Private collection.

François Hugo, George and Suzanne Ramié, Carl Nesjar, Egidio Costantini and Jacqueline de la Baume-Dürrbach collaborated with Pablo Picasso fairly frequently to create jewellery, ceramics, public monuments, glass objects and textiles.

The fact he was born into a culture – that of the Mediterranean – so historically inclined to indulgence in the pleasures of manual activity undoubtedly partly accounts for the interest Pablo Picasso always showed in the popular arts. In addition, these creations provided a highly fertile ground for artistic experimentation: they allowed him to work with materials other than those commonly used in the visual arts, for instance clay or silver; to become acquainted with practices and objects deeply rooted in the prehistoric origins of his native land, such as the pendants made from engraved pebbles and bones; and to produce his creations in working spaces other than his painter’s studios, for example the Madoura pottery workshop in Vallauris.

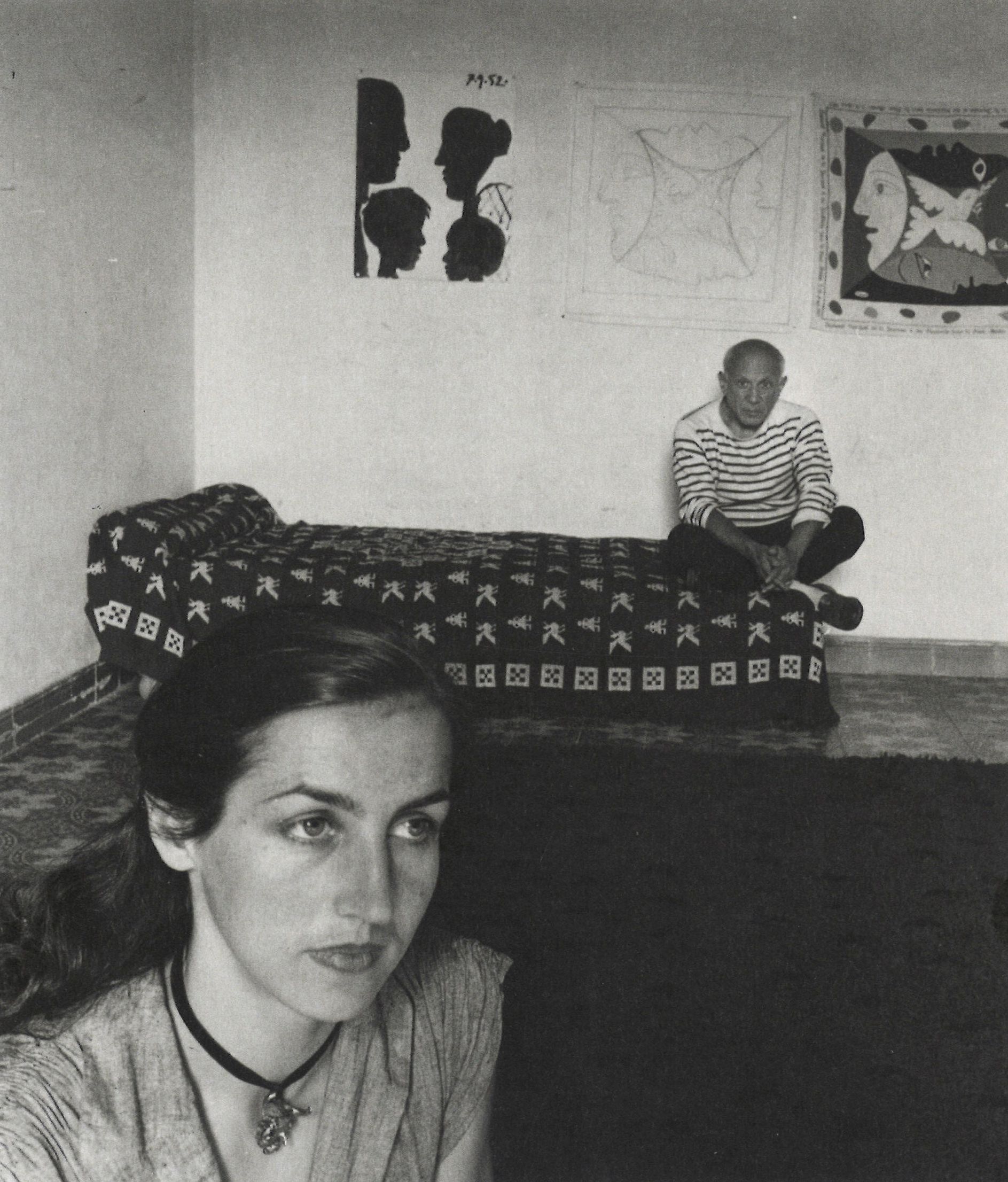

To what extent were these collaborative pieces designed to be used? There are photographs proving that some of them did have a function, or at least that they were used in the artist’s most private environment. But apart from these rare testimonies, the fact is that over the years critics, literature and museum institutions themselves have given these objects (and the sketches that preceded them) the same consideration of artworks that a drawing, a sculpture or even a painting by the artist might have, and they have joined the collections of important museums all over the world and fetched very high prices at reputed auction houses.

Françoise Gilot wearing the Satyr pendant with Pablo Picasso in the background at La Galloise, Vallauris, September 1952. Photograph by Robert Doisneau

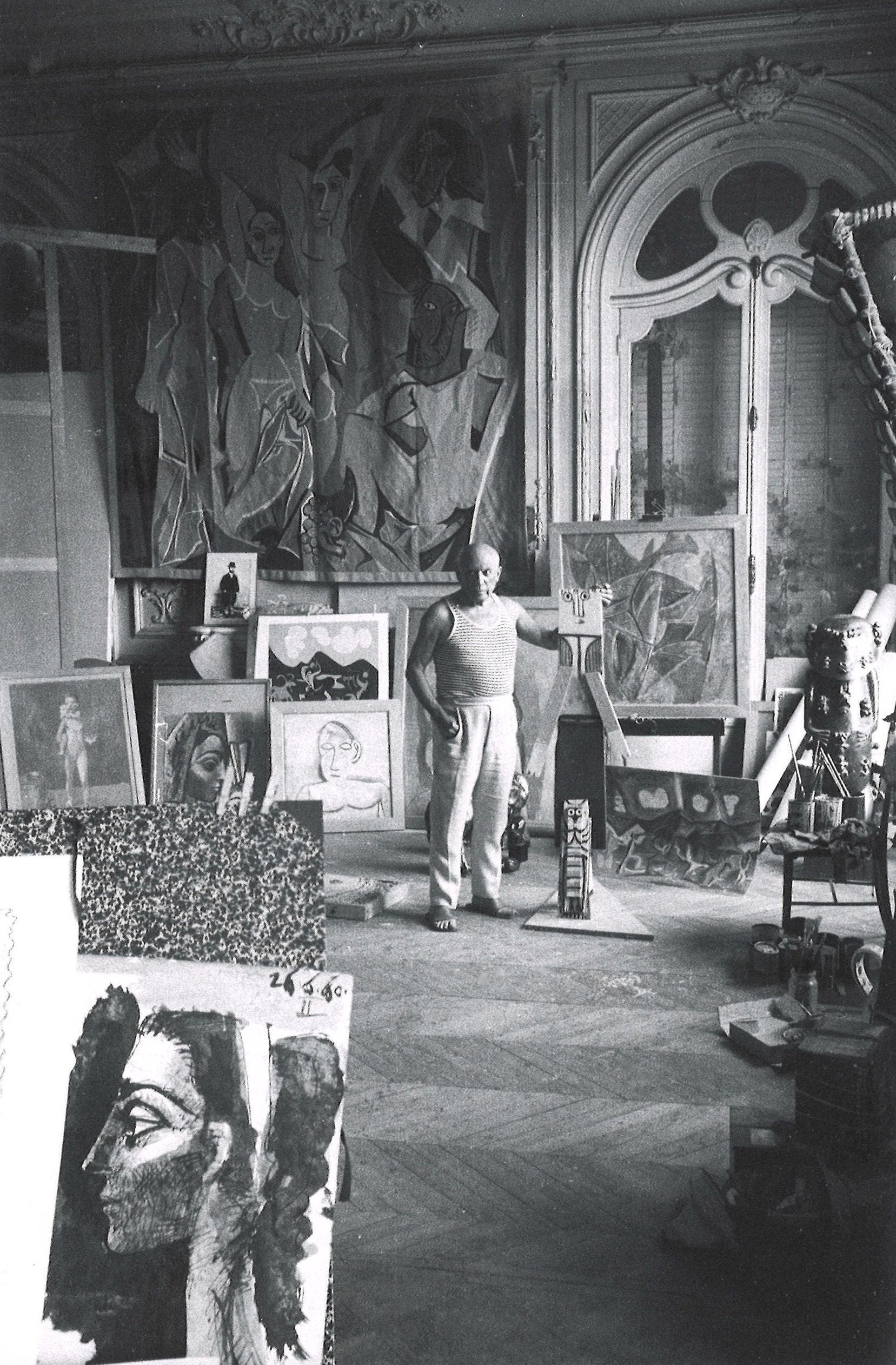

The works featured in Dialogues with Picasso. Collection 2020−2023 at the Museo Picasso Málaga include a large number of pieces of this kind. One such object is a tapestry based on the legendary picture Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), which was executed in 1958 in Jacqueline de la Baume-Dürrbach’s tapestry workshop. Authorised by the artist, the weaver took a number of artistic liberties resulting in a work that is iconographically recognisable but formally and artistically diverse. Picasso liked the tapestry so much that he decided to hang it in his studio at ‘La Californie’.

Tapestry of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon hanging on the wall of Picasso’s studio at ‘La Californie’. Photograph by Edward Quinn.